It is such a joy to go through the many photographs the team captured and to see how much the children I have met have grown and how happy they seem.

It is such a joy to go through the many photographs the team captured and to see how much the children I have met have grown and how happy they seem.

Showing posts with label Honduras. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Honduras. Show all posts

Tuesday, June 23, 2009

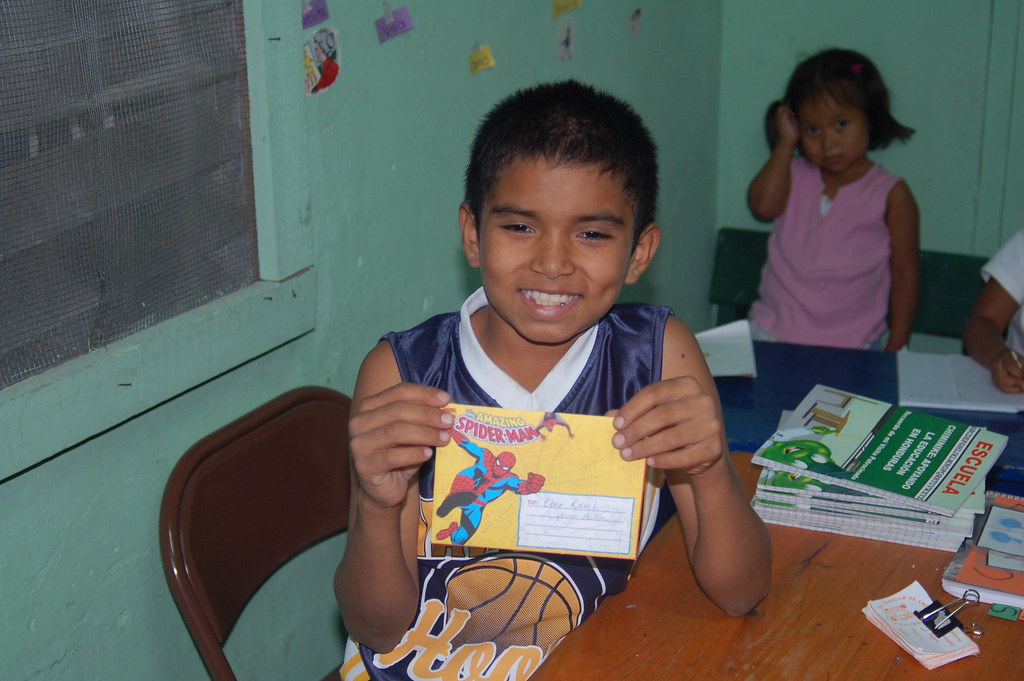

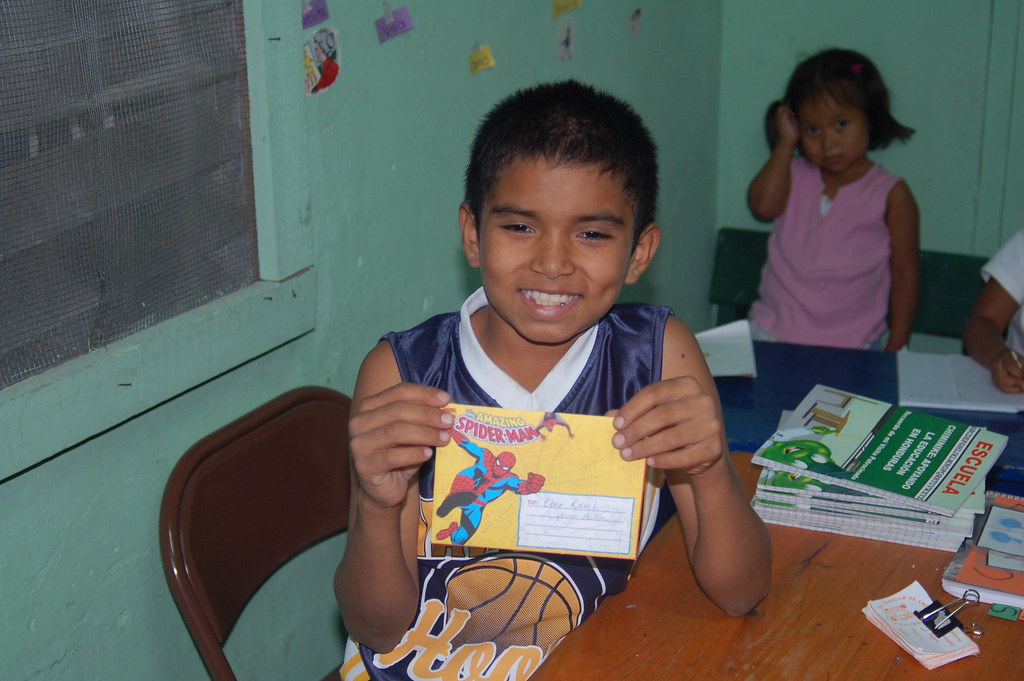

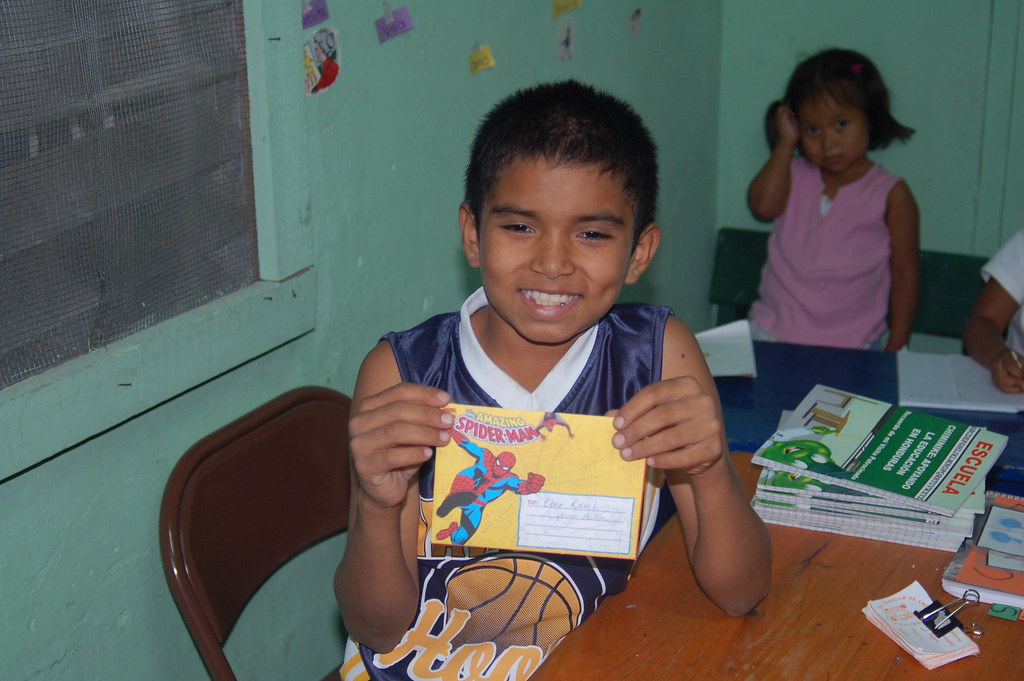

Eber at El Hogar

In early May another group of MathWorkers traveled to Honduras to help out at El Hogar de Amor y Esperanza (the Home of Love and Hope). Unfortunately, I was not a part of this third team. Still, you can read about their experiences and see many photos of the kids on the blog they maintained during the trip. Jason kindly hand delivered my letter to Eber, and even took a photo of Eber with the letter!

It is such a joy to go through the many photographs the team captured and to see how much the children I have met have grown and how happy they seem.

It is such a joy to go through the many photographs the team captured and to see how much the children I have met have grown and how happy they seem.

It is such a joy to go through the many photographs the team captured and to see how much the children I have met have grown and how happy they seem.

It is such a joy to go through the many photographs the team captured and to see how much the children I have met have grown and how happy they seem.

Thursday, October 11, 2007

Comparing Hospital Escuela to Hospitals in the Soviet Union

After reading my post on Hospital Escuela, the teaching hospital in Tegucigalpa and the only hospital in Honduras admitting patients free of charge, someone compared the conditions in Hospital Escuela to conditions in the Soviet era hospitals in Russia. Hospitals in the Soviet Union were neither clean, nor comfortable, nor were the patients treated in a terribly humane manner. Similarly to Hospital Escuela, a room in a Soviet era hospital usually housed between 5 and 12 patients with no privacy a single toilet on a given floor. Many wards, including the pediatric ward, did not allow any visitors at all. As terrible as those conditions appear to an average American, they cannot compare to Hospital Escuela and the Honduran health system.

In Communist Russia, healthcare was free including any tests, procedures or surgeries required. With very rare exceptions all hospitals and clinics were free. While shortages of medicine were not unheard of and have become more frequent since the collapse of the Soviet Union, most common medicines were usually available, and all medicine was affordable to an average citizen.

Honduras has only one hospital where a patient can stay and hope to be treated for free, and the patient still has to pay for any tests often required prior to any surgeries. Armed guards are stationed by the heavy gates of the hospital, and they decide who can go into the hospital and who cannot. Besides Hospital Escuela, Honduras does have some free or low cost clinics where poor people can be seen by a doctor or a nurse. However, any medications are not free even at these clinics, and even if the clinic has the medication in stock, which is rare, typical patients cannot afford to fill their prescriptions.

Most doctors in the Soviet Union were very well trained. Occasionally the lack of proper equipment, especially in smaller towns out in the Eastern part of the country limited the doctors’ ability to treat patients. In Honduras, a budding doctor does not have to do residency, and most of the newly graduated medical students choose to skip it.

While the Soviet Union did experience vast shortages of food in the 1920’s and 1930’s, as well as during the Second World War, resulting in starvation across vast regions of the country, there was no starvation during the 1970’s and 1980’s. Excluding high ranking officials feeding off corruption, citizens of the Soviet Union were equally rich or equally poor. In Honduras, a lot of patients admitted to the Hospital Escuela suffer from malnutrition on top of whatever their ailments might be. Many children suffer from chronic gastrointestinal problems due to lack of clean water.

I am not advocating a free healthcare system, nor do I intend to defend a Communist way of life. The Soviet Union healthcare was far from “state of the art”. Yet by comparison, an average Soviet citizen had access to much better medical treatment then an average Honduran citizen does today.

In Communist Russia, healthcare was free including any tests, procedures or surgeries required. With very rare exceptions all hospitals and clinics were free. While shortages of medicine were not unheard of and have become more frequent since the collapse of the Soviet Union, most common medicines were usually available, and all medicine was affordable to an average citizen.

Honduras has only one hospital where a patient can stay and hope to be treated for free, and the patient still has to pay for any tests often required prior to any surgeries. Armed guards are stationed by the heavy gates of the hospital, and they decide who can go into the hospital and who cannot. Besides Hospital Escuela, Honduras does have some free or low cost clinics where poor people can be seen by a doctor or a nurse. However, any medications are not free even at these clinics, and even if the clinic has the medication in stock, which is rare, typical patients cannot afford to fill their prescriptions.

Most doctors in the Soviet Union were very well trained. Occasionally the lack of proper equipment, especially in smaller towns out in the Eastern part of the country limited the doctors’ ability to treat patients. In Honduras, a budding doctor does not have to do residency, and most of the newly graduated medical students choose to skip it.

While the Soviet Union did experience vast shortages of food in the 1920’s and 1930’s, as well as during the Second World War, resulting in starvation across vast regions of the country, there was no starvation during the 1970’s and 1980’s. Excluding high ranking officials feeding off corruption, citizens of the Soviet Union were equally rich or equally poor. In Honduras, a lot of patients admitted to the Hospital Escuela suffer from malnutrition on top of whatever their ailments might be. Many children suffer from chronic gastrointestinal problems due to lack of clean water.

I am not advocating a free healthcare system, nor do I intend to defend a Communist way of life. The Soviet Union healthcare was far from “state of the art”. Yet by comparison, an average Soviet citizen had access to much better medical treatment then an average Honduran citizen does today.

Sunday, October 7, 2007

More on Eber Raul

During my stay in Honduras I asked Claudia, the director of El Hogar de Amor y Esperanza, to tell me more about Eber Raul. She told me that Eber Raul is from San Pedro Sula, a large city near the North coast of Honduras. While Eber’s mother was working all day, Eber was on the streets begging for money. He was admitted to El Hogar in February 2006.

During my stay in Honduras I asked Claudia, the director of El Hogar de Amor y Esperanza, to tell me more about Eber Raul. She told me that Eber Raul is from San Pedro Sula, a large city near the North coast of Honduras. While Eber’s mother was working all day, Eber was on the streets begging for money. He was admitted to El Hogar in February 2006.Some time ago, Claudia has taken Eber Raul back to San Pedro Sula to visit his mother, but could not leave him to stay with her. Claudia did not think Eber would be safe there, and that Eber would be sent out to beg on the streets again.

Claudia told me that once Eber’s mother came to El Hogar and wanted to take Eber back with her. Claudia did not want Eber to go—at El Hogar Eber was safe, well fed and was being educated. Eber’s mother then left saying that she did not care if Eber Raul came with her or not.

Claudia told me that once Eber’s mother came to El Hogar and wanted to take Eber back with her. Claudia did not want Eber to go—at El Hogar Eber was safe, well fed and was being educated. Eber’s mother then left saying that she did not care if Eber Raul came with her or not.Eber Raul is a very clever and outgoing boy. He is doing well in his classes. He is in first grade, but he is taking some of his classes with the second grade. He also seems to get in trouble a lot. On Friday night he was sent to go to bed early I think because he was running around without his shoes on. Saturday morning, he was one of several boys sent off to sweep the dormitory after breakfast undoubtedly due to some mischief accomplished in the morning.

Saying goodbye to Eber Raul was very difficult on several levels. Using the very few words of Spanish that I know I tried to explain that my group was leaving and going back to the United States. He just stared at me silently, and tears started rolling out of his eyes. I tried to say that I will write him letters, and that I will return, and I hugged him again. I could not make him stop crying. I had to leave and Eber Raul had to continue sweeping the dormitory.

Saying goodbye to Eber Raul was very difficult on several levels. Using the very few words of Spanish that I know I tried to explain that my group was leaving and going back to the United States. He just stared at me silently, and tears started rolling out of his eyes. I tried to say that I will write him letters, and that I will return, and I hugged him again. I could not make him stop crying. I had to leave and Eber Raul had to continue sweeping the dormitory.

Thursday, October 4, 2007

Hospital Escuela in Tegucigalpa

Today Doctor Barbara took us on a tour of Hospital Escuela, the only public hospital in the country. It is the hospital for the poor, but it is not free. The patients do not have to pay for staying at the hospital, nor do they have to pay for surgery if it is required. They do have to pay for any tests such as bloodwork, X-rays, etc. They also have to pay for their medicine. An admitted patient remains in the hospital for several weeks on average, either awaiting surgery, receiving treatment, or simply because the patient cannot pay for the required test.

From the outside Hospital Escuela is an extremely run down building, surrounded by a fence with people crowding by the gate. Apparently the guards make arbitrary decisions whom to let inside. At least four patients share a single room. There are no curtains dividing the room, hence there is no privacy. The patients must provide their own sheets, towels, toiletries, etc. They receive one very small meal a day, and thus must rely on their family to supply them with food.

During our tour we visit two wards: the pediatric ward, and the neurosurgery ward. At the pediatric ward, many children show clinical signs of malnutrition. According to Doctor Barbara, in terms of nutrition the kids usually improve while at the hospital, but usually their nutrition declines again once they return to their homes.

A grandmother cradles her two year old granddaughter in her arms. She carried her to the hospital from very far away. The girl has a problem with her lungs, and slightly swollen face and legs. Doctor Barbara suspects she has a problem with her kidneys. The grandmother spends the nights under the child’s bed since she has nowhere else to go. There is a seven year old girl sleeping in a neighboring bed. Her father is with her. Because he is a man, he cannot spend the nights at the hospital and has to go to a nearby shelter, which is not safe for him and prevents him from watching his daughter at night.

In a nearby room a 3 year old girl wrapped in essentially in rags is crying and rolling around in the crib. She is extremely malnourished, and there are no adults attending to her. There are at least 4 other children with their mothers or grandmothers in the room. The women tell us that her mother brought her in because the girl suffers from convulsions, but the mother is now in a different ward in the hospital giving birth to another baby.

At the neurosurgery ward, we meet a man who has been at the hospital since mid August awaiting surgery to remove a tumor in the back of his scull. His wife is with him, and his surgery is scheduled for tomorrow. He will require therapy after the surgery but will receive none at the hospital. Another man is awaiting multiple reconstruction surgeries to his face after he suffered a terrible accident several years ago. He has been at the hospital since mid September, and his surgery has not been scheduled yet.

We have spent only an hour at the hospital, but it left an oppressive impression. We have only seen a fraction of the horrors inside. We have not seen the people left behind to die, because their families do not want to or cannot take care of them, or because they cannot afford the required tests. There is currently no special care for the terminally ill patients. We have not seen hundreds of people waiting from 5 am for a chance to schedule an appointment at least two months ahead or more.

On our way back to El Hogar, Raul drives us past one of the private hospitals in the city. It is a shiny modern building with tinted windows and landscaped yard. Doctor Barbara informs us that its average occupancy is approximately 20%.

From the outside Hospital Escuela is an extremely run down building, surrounded by a fence with people crowding by the gate. Apparently the guards make arbitrary decisions whom to let inside. At least four patients share a single room. There are no curtains dividing the room, hence there is no privacy. The patients must provide their own sheets, towels, toiletries, etc. They receive one very small meal a day, and thus must rely on their family to supply them with food.

During our tour we visit two wards: the pediatric ward, and the neurosurgery ward. At the pediatric ward, many children show clinical signs of malnutrition. According to Doctor Barbara, in terms of nutrition the kids usually improve while at the hospital, but usually their nutrition declines again once they return to their homes.

A grandmother cradles her two year old granddaughter in her arms. She carried her to the hospital from very far away. The girl has a problem with her lungs, and slightly swollen face and legs. Doctor Barbara suspects she has a problem with her kidneys. The grandmother spends the nights under the child’s bed since she has nowhere else to go. There is a seven year old girl sleeping in a neighboring bed. Her father is with her. Because he is a man, he cannot spend the nights at the hospital and has to go to a nearby shelter, which is not safe for him and prevents him from watching his daughter at night.

In a nearby room a 3 year old girl wrapped in essentially in rags is crying and rolling around in the crib. She is extremely malnourished, and there are no adults attending to her. There are at least 4 other children with their mothers or grandmothers in the room. The women tell us that her mother brought her in because the girl suffers from convulsions, but the mother is now in a different ward in the hospital giving birth to another baby.

At the neurosurgery ward, we meet a man who has been at the hospital since mid August awaiting surgery to remove a tumor in the back of his scull. His wife is with him, and his surgery is scheduled for tomorrow. He will require therapy after the surgery but will receive none at the hospital. Another man is awaiting multiple reconstruction surgeries to his face after he suffered a terrible accident several years ago. He has been at the hospital since mid September, and his surgery has not been scheduled yet.

We have spent only an hour at the hospital, but it left an oppressive impression. We have only seen a fraction of the horrors inside. We have not seen the people left behind to die, because their families do not want to or cannot take care of them, or because they cannot afford the required tests. There is currently no special care for the terminally ill patients. We have not seen hundreds of people waiting from 5 am for a chance to schedule an appointment at least two months ahead or more.

On our way back to El Hogar, Raul drives us past one of the private hospitals in the city. It is a shiny modern building with tinted windows and landscaped yard. Doctor Barbara informs us that its average occupancy is approximately 20%.

Friends with Eber Raul

Eber Raul will be 10 years old in November, yet he is a tiny little kid. We have been getting along very well despite the fact that I usually cannot understand a word he is saying. At one point Eber pointed out his teacher to me, and told me about the classes he takes. He likes his Spanish and Science classes. Today Claudia helped me understand that Eber was asking if I would play with him after dinner. Unfortunately I had to break my promise. It started pouring during dinner, and all the younger boys were sent to bed right after the meal. Our team will be spending tomorrow night at the Farm School, so I will not be able to spend more time with Eber until Friday night, our last night here.

Sunday, September 30, 2007

Meeting Eber

Today I have finally met Eber, or Eber Raul as everyone refers to him here. It was so touching to meet him. He ran at me and hugged me even though he has never seen me before in his life. He was so thrilled to have some photos and postcards I brought him, that he carried the envelope around for the rest of the day and kept showing it to other boys and teachers. We watched some cartoons together and played with tiny toy cars. He would not stop giggling as I chased him endlessly around the yard.

Boys consider their sponsors their god parents. I would have never thought that little kids would care about someone they have never met, but yesterday Claudia told me that boys ask her all the time when their god parents would come and visit them. While all boys seek individual attention, Eber’s sheer delight in meeting me and spending some time with me touched me and at the same time made me feel very sad.

Boys consider their sponsors their god parents. I would have never thought that little kids would care about someone they have never met, but yesterday Claudia told me that boys ask her all the time when their god parents would come and visit them. While all boys seek individual attention, Eber’s sheer delight in meeting me and spending some time with me touched me and at the same time made me feel very sad.

Doctor Barbara

This afternoon Dr. Barbara McCune came to El Hogar to talk to my team about healthcare in Honduras. Dr. Barbara runs a clinic for the poor just outside of Tegucigalpa. She talked to us about the lack of affordable health care, the lack of treatment drugs, the terrible state of the only hospital in the country that will accept patients who cannot pay, and the minimal services this hospital provides to those patients. I cannot retell her stories, but I was greatly touched by the strength of her spirit, her determination and perseverance.

Dr. Barbara has been running her clinic here for over 4 years, and is not planning to leave just yet. She talked about what keeps her motivated, what keeps her working here while many have given up in frustration, what keeps her from falling into despair.

She summarized it simply as “picking her battles.” Dr. Barbara sees many people at her clinic. She cannot help them all, nor can she fix the system. Her motivation comes from the details. Small successes of her patients inspire her to continue her work. A woman working to overcome and severe depression violence at home… A woman scared but willing herself to ride a bus for 3 hours after walking for 2.5 hours to come to the city she has never been to so that her little boy receives proper treatment… One by one, her patients keep Dr. Barbara here in Honduras despite the odds.

Dr. Barbara has been running her clinic here for over 4 years, and is not planning to leave just yet. She talked about what keeps her motivated, what keeps her working here while many have given up in frustration, what keeps her from falling into despair.

She summarized it simply as “picking her battles.” Dr. Barbara sees many people at her clinic. She cannot help them all, nor can she fix the system. Her motivation comes from the details. Small successes of her patients inspire her to continue her work. A woman working to overcome and severe depression violence at home… A woman scared but willing herself to ride a bus for 3 hours after walking for 2.5 hours to come to the city she has never been to so that her little boy receives proper treatment… One by one, her patients keep Dr. Barbara here in Honduras despite the odds.

Saturday, September 29, 2007

Back to Honduras

I have safely landed in Tegucigalpa, Honduras, and now am back at El Hogar. It feels as if I was away for no longer then a week. I love being able to recognize a lot of the boys, and even being able to remember some of their names. Caesar greeted us as we drove in; he was working the gates. Later I played a little soccer with Oslin and Marlon. Brian, Tara and I also played a game involving a ball with Mario and Minor. Sadly I still have not met Eber, but Cladia promised to point him out to me. It also seems like my ability to understand Spanish has dramatically decreased since last year. I speculate that it might have something to do with me avoiding the Rosetta Stone lessons I so studiously went through prior to last years trip.

Tuesday, April 10, 2007

Eber Raul Lara Garcia

In December we, together with our friends and family, have started sponsoring the education of a little boy. Eber is a 9 year old boy who lives in Tegucigalpa, Honduras at El Hogar de Amor y Esperanza, the Home of Love and Hope. He has entered El Hogar in February, 2006, after his grandmother who has been caring for him so far could look after him no longer. He has been begging on the streets for money. Now he is safe and in the first grade.

In December we, together with our friends and family, have started sponsoring the education of a little boy. Eber is a 9 year old boy who lives in Tegucigalpa, Honduras at El Hogar de Amor y Esperanza, the Home of Love and Hope. He has entered El Hogar in February, 2006, after his grandmother who has been caring for him so far could look after him no longer. He has been begging on the streets for money. Now he is safe and in the first grade. The photo below was taken in March, 2007. Eber is on the right, with his friends, Marlon and Rigoberto.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)